A Deadly Dunt at Dullatur Station

A railway accident leading to the death of Robert Shaw of Carrickstone Farm, Cumbernauld

April 1879

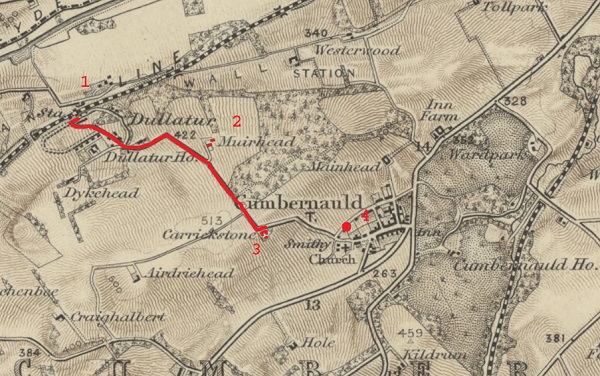

It is April 1879. In a month's time Queen Victoria will celebrate the 60th anniversary of her accession to the throne. The village of Cumbernauld, in the central belt of Scotland, is flanked north and south by railway lines. The oldest, northernmost line, opened in 1842, is operated by the North British Railway (NBR) and the southernmost line by the Caledonian railway. Three years ago the NBR opened a station at Dullatur, up the hill to the north of Cumbernauld village. At the bend in the road between the village and Dullatur station lies the 211 acre (85 ha) farm of Carrickstone, part of the Cumbernauld Estate. It is rented by Joseph Shaw (70) and his wife Agnes (50) and farmed by their three adult children, Agnes (23), Joseph (21), Janet (20) and Annie (18). Also living on the farm are teenager Robert, just turned 16, his younger brother William (13) and their cousin, George Forrester (5), illegitimate son of sister Jane (25), now married to James Stark (26), a railway porter.

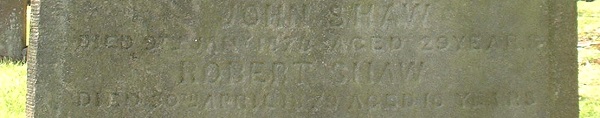

A dozen or so miles to the west is the city of Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland. James (31), the oldest surviving son of Joseph and Agnes, married Margaret Whitecross (30), daughter of the Cumbernauld Estate's factor, Andrew Whitecross, three years ago. They moved to Glasgow to operate a dairy and started a family there. They have a son, Joseph, 18 months old and a daughter, Barbara, just over a month old. A year ago James' brother, John (29) had married Agnes Main (21), from the farm up the road at Muirhead. He had been working in Glasgow as a vansman and following his marriage they set up home in Lumsden Street, Glasgow but unfortunately he died after only five days of marriage.

It is now Tuesday 29th April 1879. British troops are fighting in the Zulu Wars in South Africa, parliament is expressing concern over the number of people dying as the result of steam boiler explosions. Last year 15 people were killed and 16 injured outside buildings housing an exploded boiler. The average loss of life to a boiler explosion is 75. It is a cold day, temperatures ranging from 4 to 12 °C with little wind.

At 7.30 p.m. 16 year-old Robert Shaw catches the stopping train out of Dundas Street Station, Glasgow, (now known as Queen Street). This should allow him to get home before sunset, about an hour later. The train labours up through the steep tunnel to Cowlairs, where it will make its first stop, from which the running is fairly even all the way through to Edinburgh. The train makes three more stops, at Bishopriggs, Lenzie and Croy before arriving at Dullatur, where Robert dismounts to start his mile or so walk downhill to Carrickstone.

Did he perhaps catch sight of his brother-in-law James Stark as the train drew in to the station or, in typical teenager fashion decide that it was just too much to walk down the platform to the footbridge only to have to walk back up the platform opposite? What we do know is that he decided to cross the line behind the departing train, which no doubt concealed the sound of what The Scotsman was to report as “an express train from Edinburgh” approaching at speed on the other line.

The Glasgow Herald of May 1st 1879 reported:

A fatal accident occured late on Tuesday night to a boy about 16 years of age, named Robert Shaw, son of Joseph Shaw, Carrickstone Farm, Cumbernauld. The deceased had left Glasgow by the 7.30 P.M. train last night from Dundas Street, and on his arrival at Dullatur had attempted to cross the line when an engine coming from the east caught him and threw him a distance of about 30 yards. When picked up it was found that an arm was broken in two places, a leg terribly mutilated at the knee joint, while an aperture as large as would allow one's hand to be inserted was made in the back of his head. He was removed to his father's house, a distance of a mile, and was attended by Dr Milne, where, after suffering great agony till half-past one o'clock yesterday morning death put an end to his sufferings.

The life of Robert Shaw is recorded on the memorial stone set in Cumbernauld Old Kirkyard, joining that of his grandparents and pre-deceased siblings, eventually to be joined by that of his parents.

Postscript

Why was Robert travelling on the train on a weekday? Had be been visiting his brother and his young family? Had be been on an errand or perhaps was working there? Accomodation at his brother's would have been tight as the household probably included a dairymaid or two and maybe even a domestic maid to help out with the children. No doubt the journey would have been very familiar to him and he would have discovered all the short-cuts.

No accident enquiry was held, the facts were reported to the local Procurator Fiscal who made a submission to the Registrar of Corrected Entries on May 9 th 1879. (As it happens incorrectly, giving the wrong date for accident). Brother-in-law James Stark registered the death, being in the house at the time. Might he also have been present at the scene of the accident?

The railway must have fascinated the youngsters at Carrickstone, particularly so if their brother-in-law worked there. Robert's younger brother, William, was later to emigrate to Australia along with his brother-in-law George Main. There he found work on the railway, rising to the rank of Station Master. His eldest son was named Robert, perhaps in memory of his brother, but sadly he only lived to be five.